In EMS, we can’t take pictures of the dead. We can write about them, but we have to change the details so the person cannot be identified. I have done this on many occasions. In my head I have a photo gallery of the fallen in this opioid poisoning crisis. The photos are not blurred, the details, all of them, remembered

Each week, I add more to the collection.

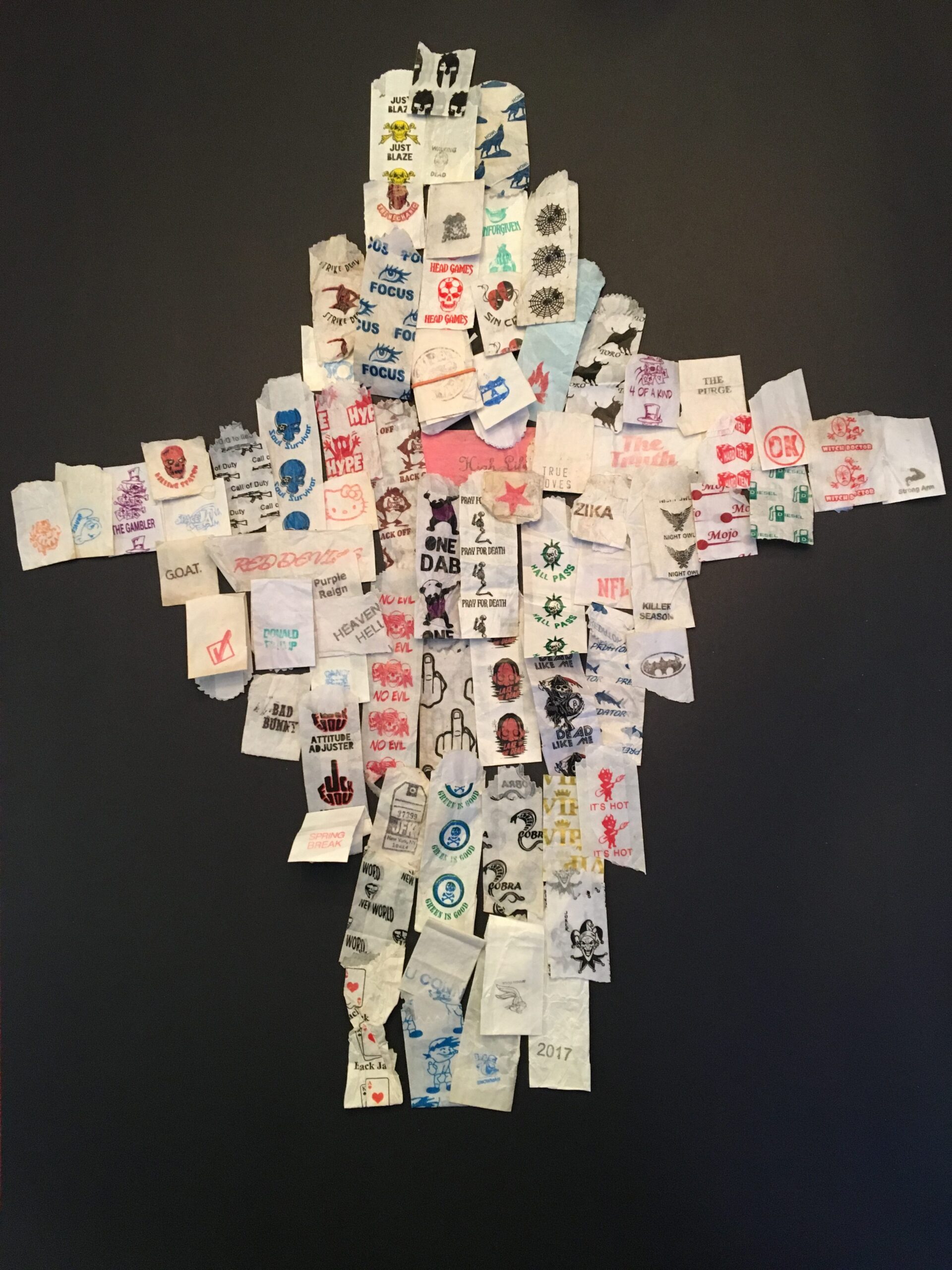

An emaciated man sits on a decrepit couch in the basement darkness, his right leg is folded up on his left knee as he probes his ankle for a vein. There is blood drawn back in the barrel. The small basement area is dirty, nearly a dozen used syringes lay on the table, along with torn heroin bags. In the corner, in a broken laundry basket is a dust-encrusted bird head — the top half of a sport mascot outfit worn long ago.

The woman who lives upstairs, heard him come in last night, and then found him unresponsive this morning. She administered two vials of naloxone, which lay now on the cement floor, and called us. The man is cold to the touch and riggored into position, the needle still in his ankle, his hand still holding the syringe.

One of 100,000 dead in a year alone. Still no end in sight.