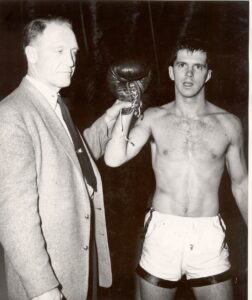

My Dad was born in 1934. He grew up in White Plains, New York in a modest house with a small yard enclosed by a white picket fence. His father worked for the telephone company and his mother was a nurse. He had a younger brother and sister, Peter and Helen, who he looked out for. He read Buck Rogers comic books and adventure classics like the Three Musketeers and The Last of the Mohicans. He played baseball in sandlots and hockey on frozen ponds. His heroes were Audie Murphy and Ted Williams. He thought Elizabeth Taylor was beautiful. His aunts, Hazel and Helen, a sportswriter and a social worker, helped his father pay for him to go to the Phillips Exeter Academy. He played football, basketball and baseball and was three times president of his class. He went to Harvard where he became a boxing champion.

In the summers he hitchhiked across the country and worked as an oil field roustabout in Oklahoma.

He met my mother at a dance at Smith College. My mother told me she fell in love with him because he was a gentleman. It impressed her that he always had something nice to say to the ladies in the cafeteria line. They married after he graduated.

He joined the Navy and finished first in his class in flight school in Pensacola, Florida, where my sister was born.

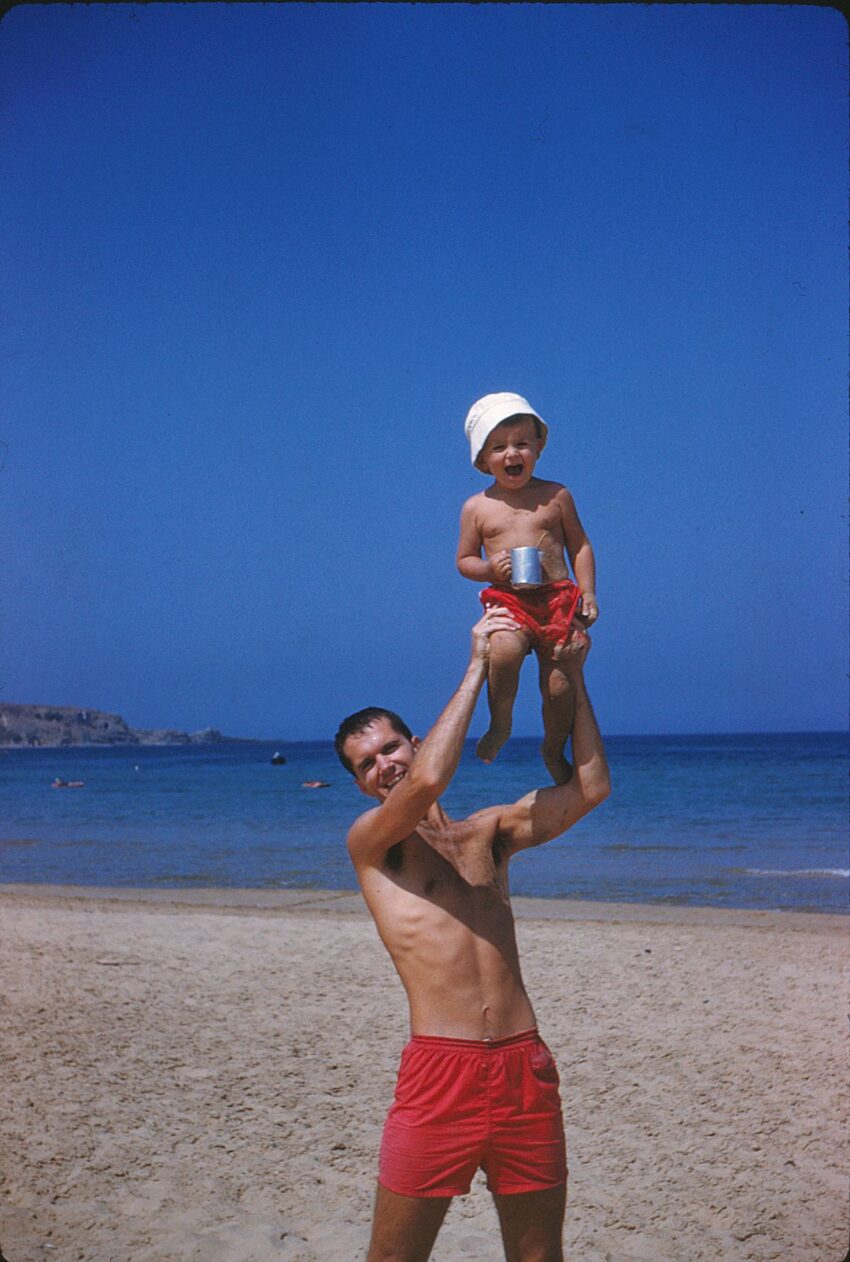

It was 1957 and when Eisenhower ordered peacetime reductions, he left the service and joined Pan American Airways where he worked in international airport operations. I was born in England in 1958. Later, my father was transferred to Istanbul, Turkey where we lived in an apartment building that looked out over the Bosphorus.

There were gypsies and dancing bears in the streets. When he was transferred to Nigeria, he quit and brought our family back to the United States where he entered a training program to become a stock broker. He bought us a home in a suburb of Hartford, Connecticut. I remember helping him seal letters into envelopes that he passed out when he went door-to-door trying to get clients. He was a member of the Civitan club. I stood with him in front of Doyle’s Drug store to sell fruitcakes to raise money for local charities. I thought he was the greatest Dad in the world. I remember him hitting a mammoth home run during a men’s softball game. He coached me in Little League baseball and YMCA basketball where we won the 8th grade championship. We vacationed first for one week a summer, then for two in a rented cottage on Nantucket Island. Once a year we went to Fenway Park to see the Red Sox play. My younger brother was born in 1966.

My dad’s firm paid for us to join the local country club where he played tennis and golf, and paddle tennis in the winter, where he and his partner became local champions. He did well at work and began to handle institutional accounts instead of retail. We moved into bigger houses. He was able to pay for me to go to Exeter and my sister to go to a local private school. He called me once a week and always asked if I was getting enough sleep and enough fruit to eat. We didn’t need to take out loans to go to college. We had a summer cottage.

Then my mother got multiple sclerosis and went from walking with a cane to a wheelchair, to bedbound. We sold our cottage. My mother, his wife of over 30 years, told me that she wished for him to one day marry a family friend whose husband was at the same time dying of cancer. He did.

When his brokerage firm closed their Hartford office and wanted my father to move to New York, he negotiated an early retirement noncompete deal where they paid him not to take his loyal clients away from them. He and his wife became avid hikers, traveling the world.

Eventually, they moved to Florida, where they both enjoyed golf. My father became a bird photographer. His pictures won awards and he even had a show or two showcasing his best work.

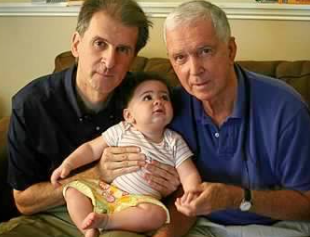

He and his wife had many grandchildren, who they loved, including my daughter Zoey (born in 2008) who was their youngest.

They proudly wore the tie dye world’s greatest grandparents t-shirts my daughter made for them. Zoey taught them how to make slime.

Once when my father had back surgery, he had to spend a few days recovering in a skilled nursing facility. All the nurses and the aides loved him because he was always courteous, always quick with a compliment or a friendly joke. It helped that they were all from the Caribbean and they noticed the pictures of his grandchildren. My brother married a woman of Trinidadian descent, and my wife is Jamaican. I thought it was great that his grandaughters enveloped him with protection.

A few years ago, his wife became concerned that my Dad’s memory was slipping, and he was declining physically. The DMV took his driver’s license away. He was angry about that, but he was still able to drive his golf cart about their retirement community, although he’d stopped playing the sport due to arthritis in his hands which he blamed on his old boxing days. When I talked to him on the phone, he was always cheerful, still asking if I was getting enough fruit to eat. But I did notice his answers were becoming more repetitive. When his wife visited her daughters, I went down to Florida and stayed with him for the week. He got tired when we went grocery shopping and I found him a place to sit by the door, while I finished up, making sure to get the tart Pink Lady apples he liked along with several kinds of berries he always put in his cereal and on his ice cream. We watched Top Gun: Maverick. My Dad, the old pilot, loved the flying sequences. He told his wife about what a good movie it was when she returned. You don’t remember we saw it in the theater two weeks ago, she told him. I’d send him highlights of my daughter’s basketball games and his wife said he would stream them over them over and over.

Another year went by. His wife said all he did was sleep and rarely went out. I visited him again for a week, and he was noticeably frailer. Sometimes he slept so long, I went into his room and watched to make certain that his chest was still rising.

Two months ago, he entered memory care. His wife was no longer able to care for him at home. He couldn’t get up off the couch by himself and had fallen several times and needed help with daily living. I wished that our family was not scattered all over the country, that we could all be around him and care for him in his home. We pitched the memory care center as a rehab place where he could get stronger. He was agreeable. He wanted to get stronger. When he walked in, moving slowly with his walker, he said to me, “This is a sad day. I put both my parents into nursing homes.”

His father had lasted only a month in a nursing home. It had killed him. On the other hand, my great grandmother had gone into a home on death’s door and lived for ten years, thriving on the community. I didn’t give my father great odds.

He called me a few days later saying he didn’t like the hotel room they were staying in. He was going to pack his bags and expected to be home by the next afternoon. In the morning he had no memory of his midnight call. Within a couple weeks he was completely bed bound.

Zoey and I flew down to Florida to visit him last week. We stayed in his home and drove over to the memory center twice a day. He would light up when he saw his granddaughter and when she kissed him and said, I love you, Grampa. Some visits were better than others. One day he was cold, his teeth chattering. The temperature in his room was 72. We raised it to 80 and got him some blankets. He felt better. Another visit he was sound asleep. They had brought him his dinner (chicken breast and green peas) which he left untouched on the tray by his bedside. Another time, he declined the cheeseburger we brought him. All he wanted, he said, was a glass of cold water.

The nurse called me early in the morning saying he had lashed out at one of the aides and told her to fuck off and that he wanted a fucking gun. I never heard him use that language before. She was surprised too, because she said he was such a nice kind man who the staff all loved. When I saw him several hours later, he was fine. Two aides came in and he was his old charming self, telling us how much he liked them, one had the prettiest hair, the other had strong muscles. They seemed to have genuine affection for him and he for them.

On the next to last day, we brought him ice cream. My daughter cut up strawberries for him. We looked at pictures from a book of his life my sister had made for him. His memory was strong that night. He told us about his summers as a child, with his siblings and cousins, swimming in Long Island Sound, fishing from the pier and playing on his grandmother’s large front lawn each night till the fireflies came out.

On the last day before we went home, Zoey hugged him and kissed him and said goodbye. We started toward the door, and she turned around and went back and hugged him again. He held her.

We hadn’t been home for two days when his wife called and said he was not responding. The hospice nurses were there and didn’t think he would last the night. She held the phone to his ear, and I told him that I loved him, that he had taught me how to be a man and how to be a father. I told him how much his granddaughter loved him, how much his family loved him.

John Canning, May 3, 1934-August 30, 2024.