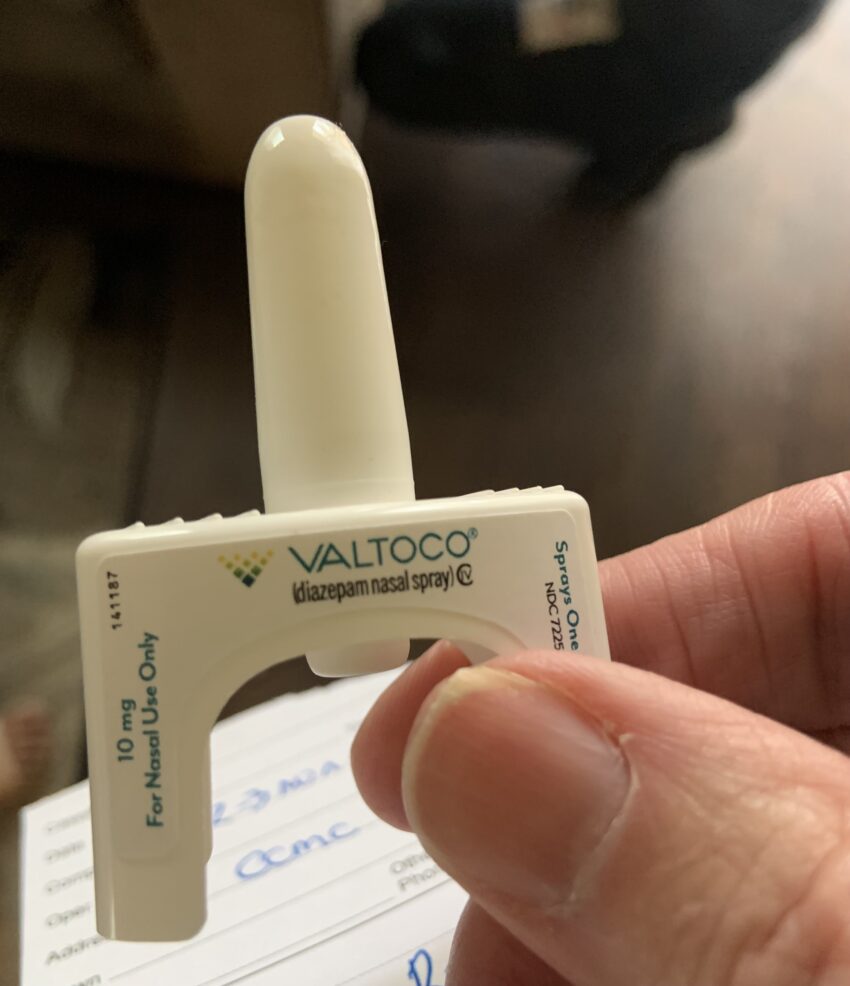

The call is for a seizure. A 9-year-old boy with epilepsy falls off the couch and is observed seizing, with full tonic-clonic activity. His mom shouts for the boy’s older sister to call 911, and then she goes to her purse and takes out the medicine his doctor prescribed for him. She sticks the nozzle of the device in the boy’s nose and pushes the plunder. We arrive two minutes later as we were just around the corner on Albany Avenue, buying chicken patties. The boy is no longer seizing and is only slightly confused. We ask what medicine the mom gave him and she hands me what looks like intranasal naloxone. I read the markings on the device. Diazepam. 10 mg. Diazepam is another name for valium, a benzodiazepine drug which can be used to stop seizures. I question the mother further about what happened and she accurately describes a generalized seizure followed by a brief postictal period of confusion.

I have heard of rectal diazepam before called Diastat, but this is my first encounter with intranasal Diazepam. With Diastat — parents have to pull down their child’s pants and insert the nozzle in the rectum before pushing the fluid. This intranasal method is so much better — quicker and clearly less invasive.

We take the patient into the hospital. The ride is uneventful.

When I started as a paramedic we could only give naloxone intravenously (IV) or intramuscularly (IM). Then when we first could give it intranasally, it involved screwing a vial into a holder, attaching an atomizer and then injecting half the spray in one nostril, and the rest in the other nostril. Then they came out with the single use concentrated naloxone intranasal device that involved simply placing the nozzle in the nostril and giving one quick push. Studies showed lay people could use this device successfully even with no training.

Recently I read the FDA just approved an intranasal epinephrine that also looks just like the naloxone and diazepam nasal sprays. Studies show the intranasal device is just as effective as an epi-pen and has the benefit of being quicker and again less invasive. Many people die of anaphylaxis because people either don’t give epinephrine or giving it too late. They speculate the intranasal device will cause people less hesitation, and they will get the epi in and working quicker before the patient gets much worse.

The FDA had also previously approved an intranasal glucagon device for hypoglycemia. A patient is unconscious with low blood sugar. The preferred treatment is to insert an IV and then administer Dextrose through the IV line. But if no paramedic is available or the paramedic can’t get an IV line, the second option was to administer glucagon intramuscularly. The medicine first required mixing a fluid and the glucagon powder. The glucagon works by stimulating the body to release sugar stores in the liver. Now, as with naloxone, diazepam, and epinephrine, one squirt in the nose and the patient hopefully is on the way to recovery.

In Connecticut EMTs (nonparamedics) can administer intranasal naloxone, and can assist patients with both intranasal and rectal diazepam, but they are not yet allowed to administer glucagon or epinephrine intranasally.

I see the day when EMTs will be able to carry and administer all of these meds intranasally, particularly if the national paramedic shortage continues to get worse.