“Endotracheal Intubation is the insertion of a tube in the trachea. Tracheal intubation is the definitive method of airway management. Endotracheal intubation allows the greatest control of the airway. It is a skill that requires extensive training and is subject to degradation if not practiced appropriately.”

Advanced Airway Management, Charles Stewart MD, FACEP, Prentice Hall 2002

**********

When I was a new paramedic, intubating made me feel bonafide. I got the tube, I was THE MEDIC. Legit.

Intubation (Intubating) means putting a plastic tube into a patient’s trachea, providing direct access for air to go in and out of the lungs, while preventing gastric contents from getting into the lungs and damaging them. Once universally considered the gold standard in airway management, there is now debate. What if the alternative airways produce better outcomes?

Endotracheal intubation—still the gold standard in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest airway management?

“Although ETI has long been considered the gold standard of airway management, with the advent of alternative airway devices, there has been a recent paradigm shift regarding the most effective device for airway control. Currently, evidence on this matter remains scarce and there is a pertinent need to conduct further large scale RCTs, in order to gather more data on the efficacy of each device on the outcomes of OHCA.” – above referenced paper

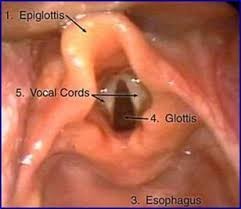

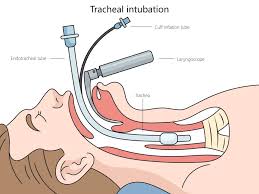

Intubation is not a simple skill. To intubate, you must insert the metal blade of a laryngoscope into a patient’s mouth and then use the blade to lift and sweep the tongue to the side so you can identify and access the vocal chords, which are illuminated by a small light bulb on the end of the blade. You must be careful not to use the patient’s teeth as a fulcrum. (As a paramedic when I am doing this, I am not standing at the head of an operating table, I am often laying prone on on a kitchen or bedroom floor.)

Once you see the chords you can pass the tube through them, careful not to go to deep. You then inflate the balloon that seals the space between the tube and the walls of the trachea. You then attach a bag-valve mask to the end of the tube, along with a C02 detector. You squeeze the bag forcing air into the tube and down into the lungs..

I immediately look at the CO2 on the monitor. If you are in the lungs you will have a nice rectangular shape along with a positive number indicating the carbon dioxide is flowing out of the lungs after each squeeze of the bag. If the line is flat, again you are likely in the esophagus.

After getting a positive reading, I then listen over each of the lungs. I want to make certain the sounds are equal on both sides. If you pass the tube too deeply into one of the mainstems of the bronchus, you will only inflate one of the lungs, so you have to pull back on the tube till it is just right.

Intubation is not the easiest skill and it is fraught with danger. A misplaced airway will kill a patient. When I started we didn’t have waveform capnography, which is the best way to confirm the tube placement. You relied on positive lung sounds and no sounds over the belly.

Over the years airway management has changed. Years ago we would try over and over to get the tube if we failed on the first attempt. We very rarely utilized a backup tube –an EOA or later a combitube, or even later an LMA, all supraglottic airways and blind insertions. SGAs anchor above the chords. They were backups and coming into an ED with a backup airway for some was an admission of skill failure. I couldn’t get the tube, I couldn’t see the chords. Nowadays, our old backup tubes are considered alternative airways and it is okay to go for them first.

Supraglottic Airways: Utilization of supraglottic airways is an acceptable alternative to endotracheal

intubation as both a primary device or a back-up device when previous attempt(s) at ETT placement

have failed. – CT EMS Protocols

Not too long ago we got a new supraglottic airway called an IGEL. IGELs are awesome. Like other SGAs, you open the mouth and insert the tube blindly. IGELs solid and go in easily. I have had great success with them. So much so that in almost all cases now, it is my preferred first choice airway. I work in a single paramedic system. Before to intubate I had to turn my back on the patient to open up my airway kit and assemble my equipment, snapping the blade on the laryngoscope handle, taking a tube out of its wrapping, inserting a stylet and attaching a syringe to the balloon.

It takes me two minutes to set up. Now with the IGEL, I have an airway in about fifteen seconds. Tear open the package, open the mouth, insert the IGEL, attach to capnography and the bag and whal-la! I have great capnography wave form. I have had a number of cardiac arrest saves utilizing the IGEL. Sure, I still like to intubate, but I rarely do unless there are more than one medics on scene.

The other problem with intubating is having to protect the tube with your life as they can be easily pushed too deeply into the lungs by aggressive bagging or pulled out completely. The worst is when you pull into the hospital and your back doors open and an eager BLS crew grabs the stretcher and yanks it out while you are still holding an attached BVM to the tube. I don’t worry as much about the IGEL coming out.

I write all of this in light of a new study that came out that suggests services with poorer historical outcomes who switched to alternate airways and moved away from ETI showed more improvement while those who continued to use ETI did not. The devil of course on all these studies is in the details. The period studied (many of them COVID years actually saw a decrease in cardiac arrest survival as perhaps people were reluctant to perform bystander CPR, more people may be arrested in their homes, and more people delayed going to the hospital when they first were stricken. Clearly more studies are needed, but the support for SGAs as an alternative is more and more convincing.

I just like the IGEL. I can focus on the patient and not worry about the tube. I know one medic who always drops an IGEL, and only later once he has the patient secure in the ambulance will switch to an ET. Me, if the IGEL is working, I keep it in, and let the hospital switch later. I would not want to go from a working airway to no airway.

Maybe I’m not as confident in my ET skills as I once was when I intubated much more regularly. I used to do 12-20 a year. Now just working part time, it’s been almost two years since I intubated anything other than a mannequin. If I was working in a service doing many more intubations, I might feel differently, but I’m not certain I would.

Maybe the ego part just doesn’t do it for me anymore.

Advanced Airway Practice Patterns and Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Outcomes