Patient cool, clammy, diaphoretic with sudden crushing chest pain, family history of MI. We do a 12-Lead ECG. If the 12-lead shows ST elevation of ≥1 mm in 2 contiguous limb leads or 2 mm of ST segment elevation in 2 contiguous precordial leads, we take the patient to a hospital capable of percutaneous coronary intervention and radio in a STEMI (ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) ALERT as well as transmitting the ECG. If all goes well, we go right up to the cardiac catheterization lab where the intervention team is waiting for us so they can put the patient on the table, thread a wire into his wrist or groin, run the wire into the heart, squirt some dye to find the culprit blocked artery, inflate a balloon to clear the occlusion, and insert a stent to support the vessel’s walls, Patient has a great outcome and is released home two days later.

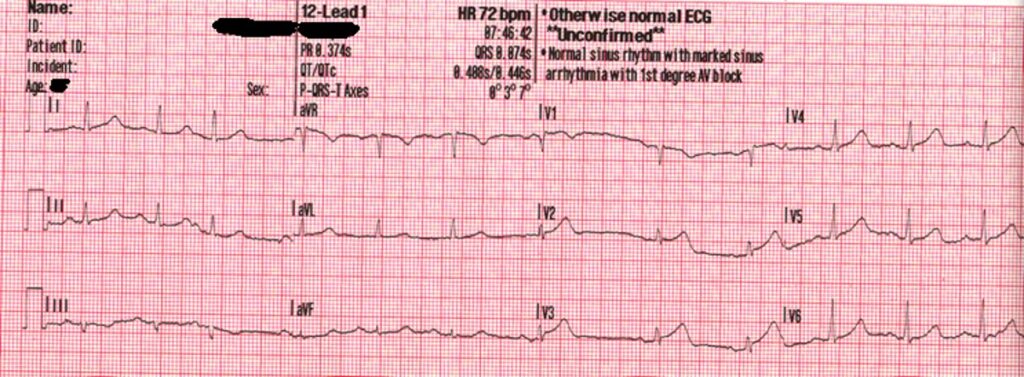

Same patient, but this time, the ECG shows only mild elevation.

You count the boxes, and it doesn’t quit meet the STEMI definition criteria of 2 millimeters in two or more precordial leads. You do serial ECGs waiting for the elevation to pop. In the hospital, the ED staff checks the patient’s blood for cardiac enzymes, and the lab result comes back forty minutes later with elevated troponin, sign of a heart attack. While the first patient has a STEMI, this patient has a NonSTEMI, commonly called NSTEMI. NSTEMIs can still go to the cath lab, but their path is often delayed. Some are treated medically; some go to the lab the next day. This particular patient (in both cases) has an acute occlusion of a coronary artery. He will do better the sooner he gets that occlusion cleared and perfusion to the affected area of the heart restored.

Whether he goes immediately or is delayed is dependent largely on someone counting the boxes (1 box per millimeter) on the ECG. Lacking the proper number of boxes (mms), this patient’s trip to the cath lab (and rapid reperfusion) is delayed and he will not fare as well.

Some medical professionals, most prominently Dr. Stephen Smith, have been calling for us to change our STEMI/NSTEMI categorization to a new one – OMI (Occlusive Myocardial Infarction)/NOMI (nonocclusive myocardial infarction), because according to research the STEMI/NSTEMI categorization misses up to 1/3 of all occlusive artery heart attacks classified as NSTEMIs.

I find their arguments convincing. They list quite a number of ECG patterns that when combined with a patient having active chest pain are suggestive of an occlusive MI, while not meeting the current technical definition of STEMI.

These patterns include:

- Patients with hyperactute T waves

- Patients with proportionate ST elevation with reciprocal changes that don’t meet STEMI criteria (often seen in high lateral)

- ST Depression in anteroseptal leads V1-3 (Suggestive of Posterior MI)

- LBBB who meet Scarbossa criteria

- Paced who meet Scarbossa criteria

- Wellens syndrome

- De winter T waves

At our hospital, we are now actively encouraging paramedics to consider these patterns and call in for a medical consult as well as transmitting. They might not always go directly to the cath lab, but we are hoping they will at least see a cardiologist at the door and have the route to the cath lab expedited.

The truth is some medics and ED doctors have already been following these guidelines, but the majority have not.

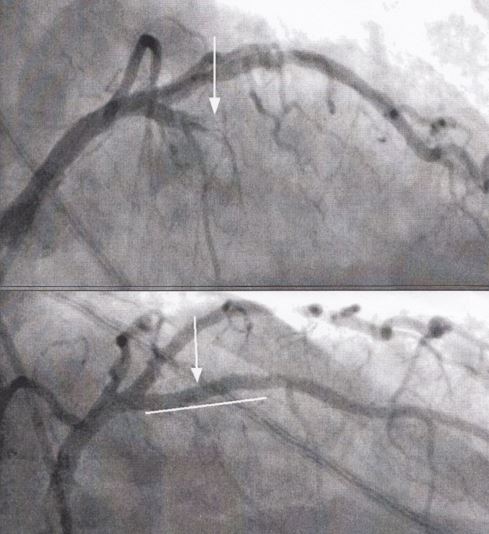

To me, the ECG posted above is a no-brainer. While not meeting the “criteria” of STEMI, it looks like a STEMI. There is elevation with reciprocal changes. The ST is disproportionate to the QRS, and the patient has a classic story. This patient went right to the cath lab, where his 100% LAD occlusion was cleared and stented. He did quite well.

Recently the American College of Cardiology has started to recognize the concept of acute coronary artery occlusion MI. Here is an excerpt from their article 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Evaluation and Disposition of Acute Chest Pain in the Emergency Department:

“The application of STEMI ECG criteria on a standard 12-lead ECG alone will miss a significant minority of patients who have acute coronary occlusion. Therefore, the ECG should be closely examined for subtle changes that may represent initial ECG signs of vessel occlusion, such as hyperacute T waves (in the absence of electrolyte imbalances or significant left ventricular hypertrophy) or ST-segment elevation<1 mm, particularly when combined with reciprocal ST-segment depression, as this may represent abnormal coronary blood flow and/or vessel occlusion. Concomitant reciprocal ST-segment depression may be visually more evident than the minor ST-segment elevation in such patients. If present, these patients should be evaluated for emergent coronary angiography as their outcomes are similar to those with more extensive ST-segment elevation.“