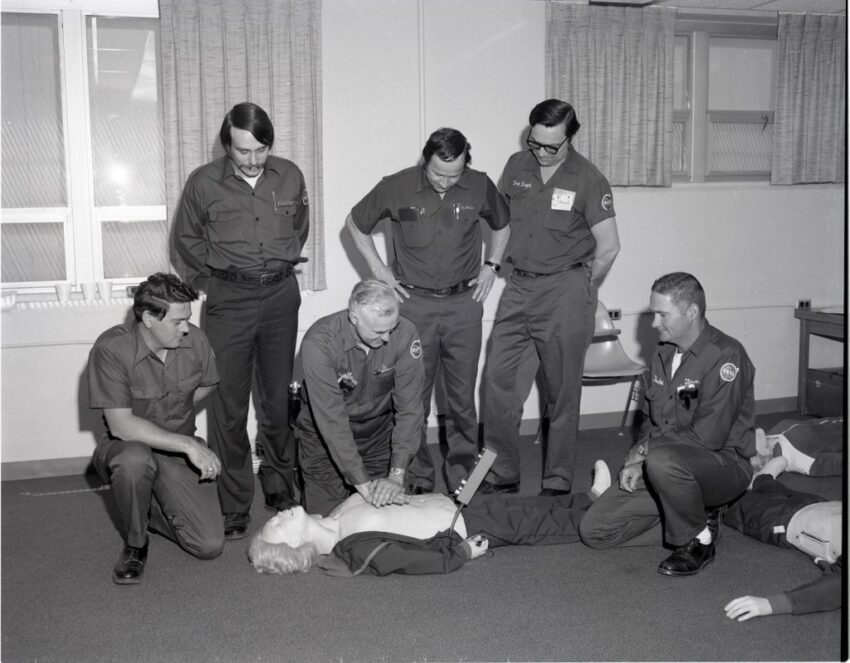

I recerted CPR, ACLS (Advanced Cardiac Life Support) and PALS (Pediatric Advanced Life Support) late in December. The certs are good for two years. That means it was the 17th time I had recerted each of these mandatory certifications. Our sponsor hospital, like all sponsor hospitals in Connecticut, requires their paramedics to have these certifications current. Our Union contract mandates that our company offer the classes to us for free, but unfortunately, my certs expired in January, and the next scheduled recert class wasn’t until April. I need to stay on top of these things better. Fortunately, I was able to take the recert classes at a nearby business that specializes in offering the classes. It was expensive, but I was the only one in each of the classes and I was able to get my certs the same day. I watched some videos, engaged in discussion with the instructor and demonstrated my skills on a mannequin in a lab.

In the past I have often felt the recerts were a waste of time. When you are doing CPR and running cardiac arrests on a regular basis, it seems unnecessary to sit through a 2 hour class on CPR and 4 hour classes on ACLS and PALS. I am only working one day a week now, and not having done a cardiac arrest for many months, I felt a little different. It didn’t hurt to run through scenarios. If when encountered with the real thing, I am that much sharper, well, that is not a bad thing. The AHA does update their guidelines, but we operate under our own protocols, which often reflect the latest scientific evidence even before the AHA changes theirs. They operate on a five year cycle; we update our protocols every two years with emergency changes in between when necessary.

In 2025, if I am still practicing which I hope to be, I will try to stay on the ball and make certain to sign up for my companies classes before my certs expire. The AHA’s next five year update may be out by then and but if there are any significant changes, they may not yet have been incorporated into the classroom material.

For all the fancy changes over the year, the bottom line has always been to provide good CPR compressions and timely defibrillation.

Speaking of protocol changes, Connecticut released its latest two year update. Here are some of the highlights:

- EMRs and EMTs may administer Naloxone IM in a dose of 0.4 mg via syringe.*

- Paramedics may administer buprenorphine to patient in precipitated withdrawal following naloxone resuscitation provided the patient meets required criteria and agrees to hospital transport.*

- The pediatric epinephrine and norepinephrine infusion rates have been lowered to 0.1-0.5 micrograms/kg/min.

- EMTs may administer 0.3 mg IM Epi via syringe for patients with asthma and impending respiratory failure.

- EMS may transport children with behavioral emergencies aged 4 to 18 directly to urgent crisis centers, provided they meet criteria and the service has sponsor hospital approval.*

- Paramedics may administer droperidol as an antiemetic, droperidol has shown utility when used for cannabinoid emesis syndrome.*

- EMTs may assist patients or caregivers with intranasal midazolam/diazepam or diazepam rectal gel administration to halt seizures.

- Ketamine dosing for analgesia, RSI induction and post-airway sedation should be based on ideal body weight (reference in protocols. Ketamine administration for sedation of violent patients should be based on actual body weight.

- The atropine dose for symptomatic bradycardia has been increased to 1 mg every 3-5 minutes to a total of 3 mg.

- Passive oxygenation (via nonrebreather) and continuous cardiac compressions should no longer be used for cardiac arrest in absence of an advanced airway.

- AEMTs may administer epinephrine IV in cardiac arrest.*

- Mechanical CPR may only be applied after 8 minutes of manual CPR.

- Sodium bicarbonate should only be administered in cardiac arrest for suspected sodium channel blocker overdoses. It should not be given for “preexisting acidosis” and hyperkalemia.

- Resuscitation should be performed on scene until ROSC or termination of efforts unless special circumstances exists such as suspected reversible cause that can only be addressed in a hospital or persistent VF/VT or PEA with high ETCO2.

- Cuffed endotracheal tubes are preferred for pediatrics over uncuffed tubes.

- Pediatric defibrillation doses should be 2j/kg, 4j/kg. 6j/kg and 8j/kg.

- Patients with rapid atrial fibrillation no longer require a sustained rate of over 150 to be treated if symptomatic.

- The preferred vagal maneuver is the modified Valsalva. Carotid massages should not be performed.

- Diltiazem dosing is no longer weight based, instead bolus 10 mg every 10 minutes with a 30 mg max.

- Prehospital blood administration can now include both positive and negative whole blood and packed red blood cells.

- Junctional tourniquets and transexamic acid (TXA) have been added to a new hemorrhage Control guideline.*

- Central lines may be accessed for cardiac arrests, vasopressor infusions and for other life-saving medications when vascular access cannot be obtained.

- Gastric tubes may be inserted in intubated patients with training and sponsor hospital approval.*

- Needle decompression may only be attempted for patients with suspected tension pneumothorax and persistent or worsening hypoxia or hypotension and/or worsening hemodynamics.

- Violent patients should be assessed using the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale prior to efforts to sedate. Ketamine should only be used for the most severely agitated patients who present an immediate risk of harm.

*Requires Sponsor Hospital Approval