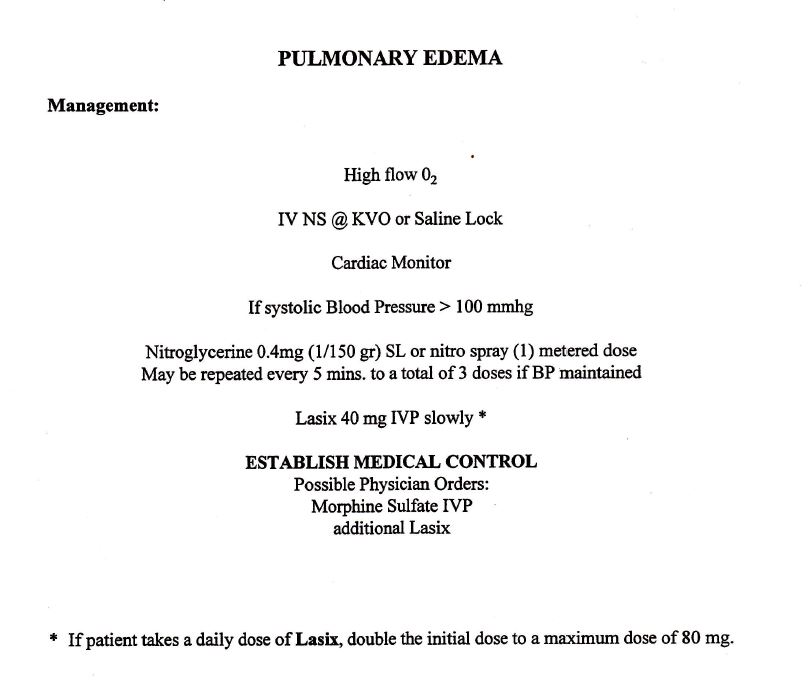

When I started as a paramedic in Hartford in January of 1995, I was given a 100-page protocol book to memorize. There were fewer than 50 protocols in the book, along with pages for 24 medications and 8 procedures. The book was approved by the two largest hospitals in Hartford. Looking through the book today, it is truly an antiquated. For instance, there was no protocol for stroke or STEMI. Paramedics didn’t do 12-lead ECGs then. There was no CPAP, no capnography, no IOs. Valium was the only benzodiazepine and morphine the only pain medicine. To give either, you had to speak directly to a physician over the radio for permission. Traumas got two large bore IVs wide open. Patients in anaphylaxis received epi 1:10,000 IV first line with a warning to push slowly. People in pulmonary edema got Lasix. Six PVCs in a minute and you got lidocaine. Asystole codes were immediately paced. Naloxone was given for coma of unknown etiology; sodium bicarb for cardiac arrests of unknown downtime. Most trauma patients received a c-collar and were strapped to a long backboard.

Several years later, all the hospitals in the north central Connecticut region came together and agreed on one set of protocols for all the hospitals in the region. Many paramedics worked for multiple services and is could be confusing for them to have to follow three different chest pain protocols. I don’t the exact year these protocols were implemented, but I know that in 2008 they went from a simple typed document to an algorithm format. The document was 222 pages, including 42 medications, 14 procedures, as well as 14 policies. At some point along the way we had protocols for spinal motion restriction, alcohol withdrawal, stroke and STEMI, CPAP, and termination of cardiac arrest resuscitation on scene. We carried Cardizem for rapid a-fib, fentanyl for pain, intranasal naloxone, and Haldol and midazolam for violent emotionally disturbed patients. Instead of giving D50 to hypoglycemic patients we switched to D10.

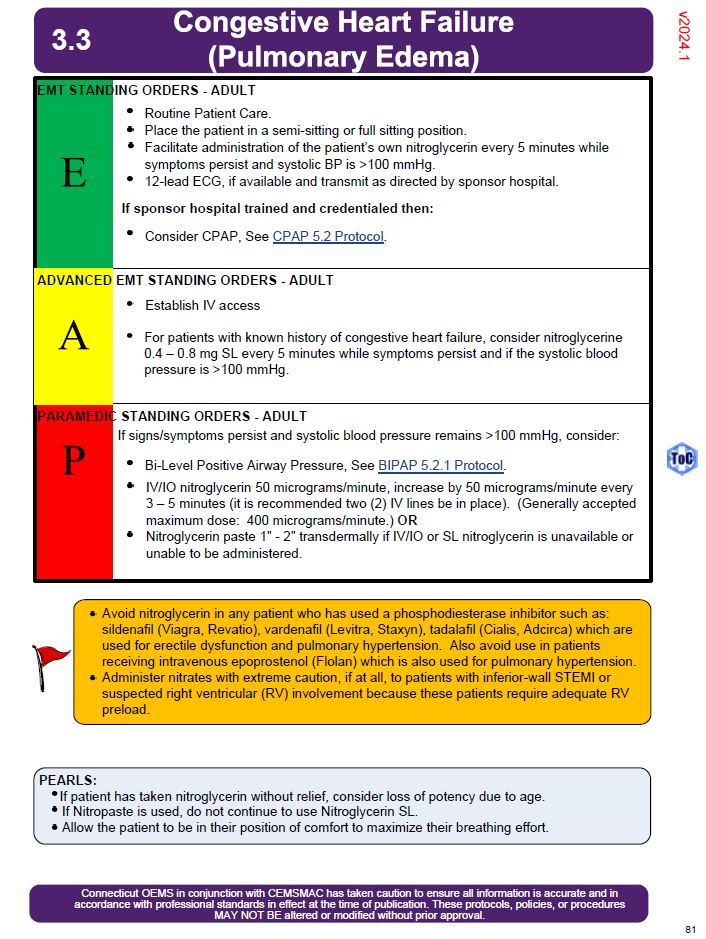

In 2016, the state of Connecticut unified all EMS services with statewide protocols, which adopted a format of each protocol starting at the EMT level and then moving up to paramedic. The first document had 170 detailed pages, including 51 medications. These protocols are now updated every year. The 2024 document is 237 pages including 56 medications. Today there are protocols for whole blood administration, buprenorphine for opioid withdrawal and ketamine both for sedation and pain. We give Ancef, an antibiotic for open fractures and TXA for traumatic hemorrhage. Nearly every protocol is on standing order with no need to consult medical control for approval.

I’m sixty-six years old now and sometimes I must consult the protocols before I give a drug to make certain I am following the latest guidelines. Norepinephrine is now our go-to-vasopressor. We don’t give solumedrol for allergic reactions anymore. The doses for many medications such as atropine, ketorolac, Cardizem and midazolam have changed multiple times. I have to put my glasses on to read the protocols. I tell my patients who wonder why the paramedic taking care of them is looking at his phone before acting, I tell them protocol dictates that I consult the protocols before giving you this medication.

I only work one day a week now, so I can go quite some time before I use many of the protocols. I’m not as fast as I used to be, which can be a good thing, although I wish I was more on my game like back when I was working 70 hours a week on the road. I don’t know how many more years I have left, how many new protocols I will have to learn, what new drugs we will see in the future, what old drugs we will say goodbye to.

A doctor friend of mine told me there is an old saying in medicine: Half of what we know is wrong; we just don’t know which half.

At least we have a process in place, always evaluating the latest scientific evidence and literature, reviewing each protocol, trying to do right by the people we care for.